Buy the book from Baylor Press | Bookshop | Amazon

Use code “17FALL24” at baylorpress.com to receive free shipping and 20% off.

Endorsements

“Words for Conviviality embodies a unique project: a cultural and technological history of a particular American era that is also a handbook to living more wisely in our digital age. Jeffrey Bilbro has written a wonderful, provocative, and illuminating book.”

~Alan Jacobs, The Jim and Sharon Harrod Endowed Chair of Christian Thought and Distinguished Professor of Humanities in the Honors Program, Baylor University

Description

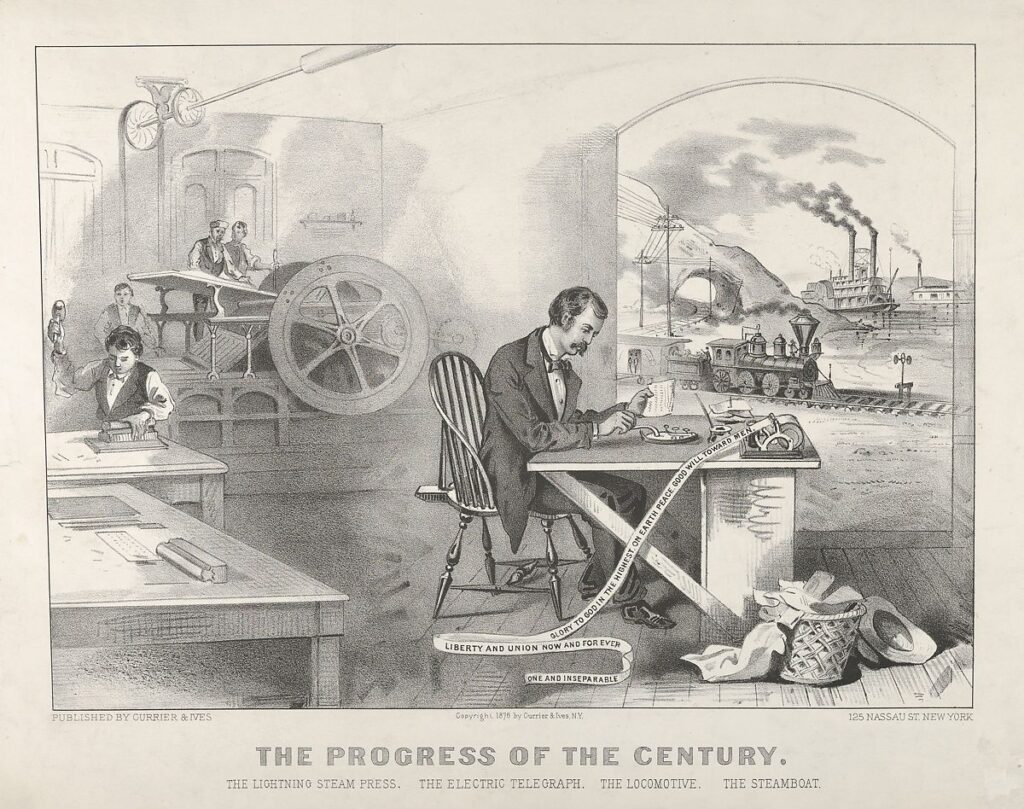

Radical innovations in communications technologies are transforming culture and disrupting journalism and publishing. Fierce partisan and geographic divides are fueling political realignment. Theological disputes are undermining the institutional church while spiritual energy is being redirected into new religious movements and cults. These statements describe our current situation, but they apply equally to 1850s America.

The industrialization of print technologies in the early nineteenth century transformed print culture in ways that parallel the transformation of reading wrought by the digital revolution. Understanding how a previous era was shaped—and in some ways warped—by the assumptions print technology engendered may enable us to recognize more clearly how our own verbal habits and practices are formed and deformed by our enmeshment in digital technologies. Perhaps the convivial reading practices that some antebellum authors imagined can guide us toward healthier ways of reading today.

On the eve of the Civil War, the printing press had become a subject of fierce dispute. Just a few generations earlier, during the excitement of the Revolutionary War and the drafting of the Constitution, printing was almost universally seen as a good, a technology that was the sine qua non of the American experiment. But by the late antebellum period, print’s products seemed a mixed bag: print circulated news and stories throughout the nation, and it inflamed partisan and regional differences; print diffused the Bible, and it reified sectarian divides; print spread scientific discoveries, and it lent legitimacy to quack medicine.

In The Confidence Man Herman Melville stages an exchange that encapsulates contemporary disputes about print technologies. Two con-men argue over which press, the printing press or the wine press, produces the true antidote to polarization and tyranny and ignorance. While Frank claims the printing press is an “iron Paul,” an “Advancer of Knowledge,” and a “Defender of the Faith,” Charlie considers it akin to an erratic Colt revolver and a mob boss like Jack Cade. To promote “conviviality” Charlie recommends the “cheery benediction of the bottle.” Charlie’s alcoholic conviviality is clearly flawed, but can the printing press foster authentic community and a healthy civil society?

Frank’s optimism about print had some warrant. In part, it was fueled by the general American faith in the progressive power of technology. More particularly, the American revolutionaries bequeathed a potent myth to subsequent generations about the power of print to unify the nation and diffuse republican virtue. The supreme authorities in the early republic were printed texts, and in the relative absence of authoritative institutions, print took on an outsized importance. But steam-powered printing technologies made texts cheaper and more abundant, and the printed word that had once unified the colonies became an atomizing force, one that served to fragment culture, church, and union.

Industrial printing technologies in the first half of the nineteenth century finally realized the promise of Gutenberg’s invention—texts were actually becoming reliable, standardized, and accessible—and yet the consequences of this realization were unexpectedly mixed—misinformation spread, discourse fragmented, and readers suffered from information overload. Today, we tend to think such problems are the result of the digital revolution, but antebellum Americans experienced them first. The printing press amplified charlatans, cult-leaders, and sensational stories more than it diffused republican virtue. Improving print technologies didn’t improve the signal-to-noise ratio; it amplified noise.

Yet when powerful new verbal technologies come along, our only options are not either booster optimism or resigned pessimism. We have alternatives to seeing print—and now pixels—as either an iron Paul or a Colt’s revolver. And some of the most helpful guides in charting a path toward genuinely convivial modes of reading are the literary authors who lived through the antebellum industrialization of print. These authors experienced the powers and perils of the steam-powered printing press, and they sought to understand its effects through the most fundamental tool that language provides: metaphor. Evocative metaphors are a potent way to raise cultural awareness regarding the hidden affordances and subtle nudges that are latent within dominant communications technologies.

The argument of my book follows a pilgrimage with three stages. Each stage considers a set of metaphors that antebellum authors deployed to answer three underlying questions: What does industrial print tempt optimistic readers to imagine themselves as? What does it lead its victims to fear they will become? And what alternative metaphors might ground more convivial reading?

The metaphors of hope that I discuss in the third stage suggest that to wield textual technologies well, we need to develop cultural practices and institutions that strengthen our relationships with one another and our commitment to a common good. We need to be tied more deeply to others and to our places in order to respond to the atomizing pressures of print and pixel. Instead of developing new technologies to solve the problems that technologies have caused, these authors propose that we develop better readers—readers who are more attuned to the power of the textual technologies they use and better able to imagine and practice healthy, convivial forms of discourse. These authors obviously did not eschew industrialized print; they did not simply give up on the technologies of their day. Rather, they developed metaphors that might inspire us to beat textual swords—or Colt revolvers—into plowshares.

I gave a 15 minute talk drawn from this book at John Brown University that gives a thumbnail sketch of the book’s narrative.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Trust, Watersheds, and America’s Industrial Print Culture

26 Theses on Textual Technologies

Section One: Utopia, or What does industrial print tempt optimistic readers to imagine themselves as?

- 1. Transparent Eyeballs (Emerson)

- 2. Men of Adamant (Hawthorne)

- 3. Encyclopedists and Map-Plotters (Melville)

- 4. Celebrities (Whitman)

- 5. Benevolent Bosses (Twain)

Section Two: Dystopia, or What does industrial print lead its victims to fear they will become?

- 6. Loose Fish (Melville)

- 7. Macadamized Minds (Thoreau)

- 8. Commodities (Dickinson)

- 9. Slaves (Douglass)

Section Three: Hope, or What alternative metaphors might orient more convivial reading?

- 10. Walkers (Thoreau)

- 11. Conversationalists (Fuller)

- 12. Friends (Hawthorne)

- 13. Cross-Bearers (Melville)